Brian G. Marsden (1937-2010)

相信大部分关注小行星彗星发现的朋友都熟悉他了,他走了,一个时代结束了,未来爱好者凭借

自制望远镜目视发现彗星的机会也越来越渺茫了!

以下摘自《天空和望远镜》杂志

Word rocketed through the astronomical community today that Brian Marsden had died after a prolonged illness.

Marsden served as the long-time director of the IAU's Central Bureau of Astronomical Telegrams (until 2000) and its Minor Planet Center (until 2006), positions that effectively made him and his small staff the worldwide clearinghouse for astronomical discoveries.

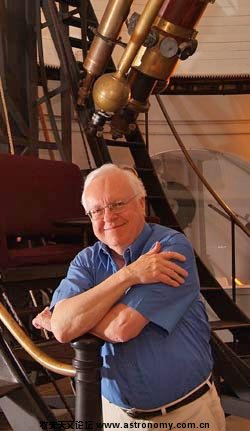

Astronomer Brian Marsden stands next to the 15-inch "Great Refractor," housed a few steps away from his office at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

CFA / Harold Dorwin

We at Sky & Telescope had a special closeness to Marsden, and not simply because his office at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics was within easy walking distance. He was perpetually busy, his desk a maelstrom of paperwork piled in chaotic-looking bundles that defied logical organization. Yet he always found time to answer our questions, often stretching what should have been a quick, 5-minute update into wide-ranging chats that would go on for a half hour or more.

One thing I'll remember most was his encyclopedic knowledge of the solar system and its contents. Whether dates and places or eccentricities and semimajor axes, he had uncanny recall. I'll also treasure his support of amateur astronomers and the value of the high-quality observations they often made and reported to him.

As it turns out, a few years ago Marsden wrote down the highlights of his long and distinguished career "just in case." Earlier today Gareth Williams, assistant director of the MPC (and Marsden's son-in-law), added some updates and posted the autobiographical reflection as a Minor Planet Electronic Circular. What follows is a somewhat shorter version of that.

No doubt many of you knew Marsden personally or through his many contributions to solar-system dynamics. If so, feel free to add a comment at the end.

Brian Geoffrey Marsden was born on August 5, 1937, in Cambridge, England. His father, Thomas, was the senior mathematics teacher at a local high school. It was his mother, Eileen (nee West), however, who introduced him to the study of astronomy, when he returned home during his first week in primary school in 1942 and found her sitting in the backyard watching an eclipse of the Sun. What most impressed the budding astronomer was not that the eclipse could be seen, but the fact that it had been predicted in advance, and it was the idea that one could make successful predictions of events in the sky that eventually led him to his career.

When, at the age of 11, he entered the Perse School in Cambridge he was developing primitive methods for calculating the positions of the planets. Together with a couple of other students he formed a school Astronomical Society, of which he served as the secretary. At the age of 16 he joined and began regularly attending the monthly London meetings of the British Astronomical Association. He quickly became involved with the Association's Computing Section, which was known specifically for making astronomical predictions other than those that were routinely being prepared by professional astronomers for publication in almanacs around the world.

He was an undergraduate at New College, University of Oxford. In his first year there he persuaded the British Astronomical Association to lend him a mechanical calculating machine, allowing him thereby to increase his computational productivity. By the time he received his undergraduate degree, in mathematics, he had already developed somewhat of an international reputation for the computation of orbits of comets, including new discoveries. He spent part of his first two undergraduate summer vacations working at the British Nautical Almanac Office.

After Oxford, he took up an invitation to cross the pond and work at the Yale University Observatory. He had originally planned to spend just a year there carrying out research on orbital mechanics, but on his arrival in 1959 he was also enrolled as a Yale graduate student. With the ready availability of the university's IBM 650 computer in the observatory building, he had soon programmed it to compute the orbits of comets. Recalling his earlier interest in Jupiter's moons, he completed the requirements for his Ph.D. degree with a thesis on The Motions of the Galilean Satellites of Jupiter.

Brian Marsden joined the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in 1965 and became director of the IAU's Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams in 1968.

S&T: Dennis Milon

At the invitation of director Fred Whipple, he joined the staff of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory in Cambridge (the one in Massachusetts) in 1965. Whipple was probably best known for devising the "dirty snowball" model for the nucleus of a comet a decade and a half earlier. At that time there was only rather limited evidence that the motion of a comet was affected by forces over and above those of gravitation (limited because of the need to compute the orbit by hand), and the Whipple model had it that those forces were due to the comet's reaction to vaporization of the cometary snow or ice by solar radiation. Marsden therefore developed a way to incorporate such forces directly into the equations that governed the motion of a comet. It is noteworthy that the procedure devised and developed by Marsden is still widely used to compute the nongravitational effects of comets, with relatively little further modification by other astronomers.

The involvement of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory with comets had been given a boost, shortly before Marsden's arrival there, by the transfer there from Copenhagen of the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams, a quaintly named organization that was established by the International Astronomical Union soon after its founding in 1920. The CBAT is responsible for disseminating information worldwide about the discoveries of comets, novae, supernovae and other objects of generally transient astronomical interest. It is the CBAT that actually names the comets (generally for their discoverers), and it has also been a repository for the observations of comets to which orbit computations need to be fitted.

Marsden succeeded Owen Gingerich as the CBAT director in 1968. He was joined by Daniel Green as a student assistant a decade later, and Green took over as CBAT director in 2000. Until the early 1980s the Bureau really did receive and disseminate the discovery information by telegram (with dissemination also by postcard Circular), though email announcements then understandably began to take over. The last time the CBAT received a telegram was when Thomas Bopp sent word of his discovery of a comet in 1995. Since word of this same discovery had already been received from Alan Hale a few hours earlier by email, the object was very nearly just named Comet Hale, rather than the famous Comet Hale-Bopp that beautifully graced the world's skies for several weeks two years later.

The comet prediction of which he was most proud was of the return of Comet Swift-Tuttle, associated with the Perseid meteors each August. It had been discovered in 1862, and the conventional wisdom was that it would return around 1981. He followed that line for much of a paper he published on the subject in 1973. He had a strong suspicion, however, that the 1862 comet was identical with one seen in 1737, and this assumption allowed him to predict that Swift-Tuttle would not return until late 1992. This prediction proved to be correct, and this comet has the longest orbital period of all the comets whose returns have been successfully predicted.

Although the CBAT also traditionally made announcements of the discoveries of asteroids that came close to the earth, the official organization for attending to discoveries of asteroids is the Minor Planet Center. Also operated by the International Astronomical Union, the MPC was located until 1978 at the Cincinnati Observatory. In that year the IAU asked Marsden also to take over the direction of the MPC. At the end of 1989, Gareth Williams joined the MPC staff and later became its associate director.

The advances in electronic communication during the 1990s also permitted improvements in MPC operation. Perhaps the most important of these was the online introduction, in 1996, of the Near-Earth Object Confirmation Page. This draws attention to candidate Earth-approaching objects in need of follow-up observations as soon as they have been reported to the MPC.

In 1998 Marsden gained a certain amount of notoriety by suggesting that an object called 1997 XF11 could collide with Earth. But he did this as a last-ditch effort to encourage the acquisition of further observations, including searches for possible data from several years earlier. The recognition of some observations from 1990 made it quite clear that there could be no collision with 1997 XF11 during the foreseeable future. Without those 1990 observations, however, the object's orbit would have become very uncertain following a close to moderate approach to Earth in 2028. Indeed, Marsden correctly demonstrated that there was the possibility of an impact in 2040 and in several neighboring years. He was thereby able eventually to persuade his principal critics routinely to perform similar uncertainty computations for all near-earth objects as they were announced.

Marsden was particularly fascinated by a family of comets, known as the Kreutz group, that pass close to the Sun. The discovery of three more of these sungrazing comets in the mid-20th century led him to undertake a detailed examination of how the individual comets might have evolved from each other. He published this examination in 1967, following it up with a further study in 1989 involving a more recent bright Kreutz comet, as well as several much fainter objects that had been detected from Sun-observing coronagraphs out in space. Beginning in 1996, these were being found by the SOHO coronagraphs at rates ranging from a few dozen to more than 100 per year. Unfortunately, the faintness of the comets and the poor accuracy with which they could be measured made it difficult to establish their orbits as satisfactorily as Marsden would have liked. More significantly, however, he was able to recognize that the SOHO data also contained another group of comets with similar orbits, these comets now known as members of the "Marsden group". Unlike the individual Kreutz comets, which have orbital periods of several centuries, it seems that the Marsden comets have orbital periods of only five or six years.

Although their views on Pluto's status were worlds apart, Clyde Tombaugh (left) and Brian Marsden were all smiles during this meeting outside Harvard Observatory in September 1987.

S&T: J. Kelly Beatty

Another series of astronomical discoveries that greatly interested him were what he always called the "transneptunian objects", though many of his colleagues have insisted on calling them "objects in the Kuiper Belt". When what those same colleagues considered to be the first of these was discovered in 1992, Marsden immediately remarked that this was untrue, because Pluto, discovered in 1930 and admittedly somewhat larger in size, had to be the first. More specifically, he was the first to suggest, correctly, that three transneptunian objects discovered in 1993 were exactly like Pluto in the sense that they all orbit the Sun twice while Neptune orbits it thrice. This particular recognition set him firmly on the quest to "demote" Pluto. Success required finding transneptunian objects more comparable to Pluto in size, something that finally happened in 2005 with the discovery of Eris. At its triennial meeting in 2006 in Prague, the IAU voted to designate these objects, together with the largest asteroid, Ceres, and two other transneptunian objects now known as Makemake and Haumea, members of a new class of "dwarf planet."

It was also at the IAU meeting in Prague that Marsden stepped down as MPC director, and he was quite entertained by the thought that both he and Pluto had been retired on the same day. While he remained working at the MPC (and also the CBAT) in an emeritus capacity, the directorship was passed to Timothy Spahr, who joined the MPC in 2000.

Marsden served as an associate director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics for 15.75 years from the beginning of 1987 (the longest tenure for any of the Center's associate directors). He was chair of the Division of Dynamical Astronomy of the American Astronomical Society during 1976-78 and president of the IAU commissions that oversaw the operation of the Minor Planet Center (1976-79) and the Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams (2000-03). He continued to serve subsequently on the two solar-system nomenclature committees of the IAU, being the perennial secretary of the one that decides on names for asteroids. Although known worldwide as a theorist and dynamicist, he shares discovery credit (with Nikolai Chernykh) for asteroid 37556 Svyaztie.

Among the various awards he received from the U.S., U.K., and other European countries, the ones he particularly appreciated were the 1995 Dirk Brouwer Award (named for his mentor at Yale) of the AAS Division on Dynamical Astronomy and the 1989 Van Biesbroeck Award (named for an old friend and observer of comets and double stars), then presented by the University of Arizona, now by the AAS, for service to astronomy. |

|