Dispatch from Libya: the courage of ordinary people standing up to Gaddafi

直击利比亚:利比亚人民反抗卡扎菲的决心和勇气

Chris McGreal, a veteran of 25 years of conflict, reveals why Libya's revolution is one of the most inspiring he has witnessed

Chris McGreal,一位具有25年战斗经验的老兵,将告诉你为何利比亚革命是他所经历的最令人激动的事情之一。

原发:卫报

作者: Chris McGreal作于Benghazi,写于2011年4月23日

翻译:匿名志愿者

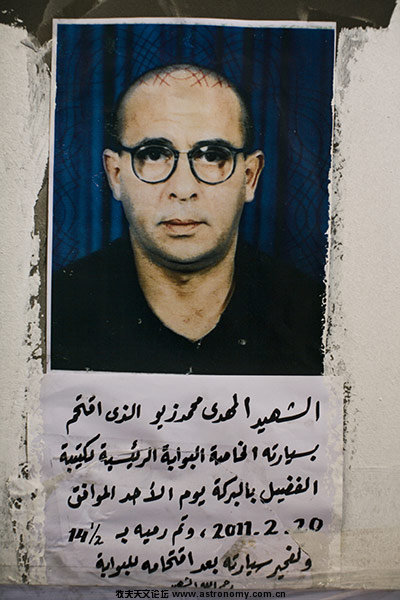

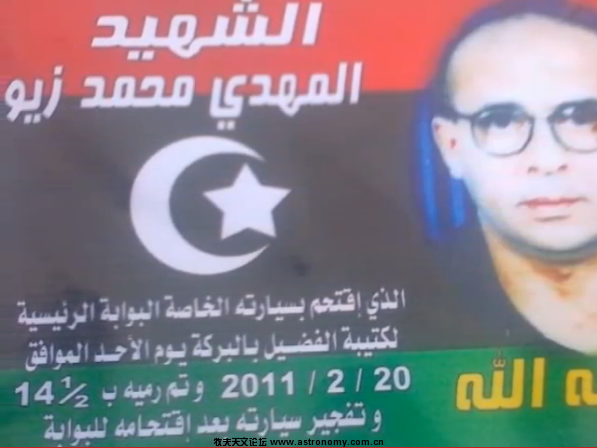

英国记者Guy Martin的照片:班加西英雄Mahdi Ziu

The Middle East. A man with a car fashioned into a bomb. He disguises his intent by joining a funeral cortege passing the chosen target. At the last minute the man swings the vehicle away, puts his foot down and detonates the propane canisters packed into the car.

中东。一名男子,驾驶着一辆已被改装成炸弹的汽车。他悄悄加入一列途经所选目标的葬礼队伍,以免被人察觉。在最后一刻,他突然转向,用脚一蹬,引爆了车上的丙烷罐。

It all sounds horrifyingly familiar. Mahdi Ziu was a suicide bomber in a region too often defined by people blowing up themselves and others. But, as with so much in Libya, the manner of Ziu's death defies the assumptions made about the uprisings in the Arab world by twitchy American politicians and generals who see Islamic extremism and al-Qaeda lurking in the shadows. Ziu's attack was an act of pure selflessness, not terror, and it may have saved Libya's revolution.

爆炸声令人毛骨悚然,却也习以为常。按照通常的定义,Mahdi Ziu是一名自杀式袭击者,就是那些把自己和他人一起炸死的人。然而,像利比亚许许多多其他人一样,Ziu死亡的方式向美国政客和大众对阿拉伯世界发生的起义的认识是一个挑战--他们曾经认为这里面有伊斯兰教极端主义和基地组织的影子。

一张珍贵的照片,法国文学家、哲学家列维在Mahdi Ziu炸开班加西军营大门的车前。列维见本文附注

In the first days of the popular uprising he crashed his car into the gates of the Katiba, a much-feared military barracks in Benghazi, where Muammar Gaddafi's forces were making a last stand in a hostile city. At that time the revolutionaries had few weapons, mostly stones and "fish bombs" — TNT explosive with a fuse that is more usually dropped in the sea off Benghazi to catch fish. The soldiers had heavy machine guns and the revolutionaries, often daring young men letting loose their anger at the regime for the first time, were dying in their dozens as they tried to storm the Katiba.

在起义发生的开始几天,他驾车冲进Katiba的大门。那里是班加西一处令人望而生畏的兵营,卡扎菲的军队正在那里负隅顽抗。彼时义军几乎手无寸铁,至多是石块和“鱼弹”——炸药装上导火索,经常被投到班加西附近的大海里炸鱼用。government军拥有重型机枪,而起义者,通常是那些首次将怒火撒向government的勇敢的年轻人,在猛攻Katiba时成群成群地死去。

Then Ziu arrived, blew the main gates off the barracks and sent the soldiers scurrying to seek shelter inside. Within hours the Katiba had fallen.

然后Ziu到了,他炸毁了Katiba的大门,government军纷纷退到里面寻找掩护。几个小时后,Katiba兵营就被攻下了。

Ziu was not classic suicide-bomber material. He was a podgy, balding 48-year-old executive with the state oil company, married with daughters at home. There was no martyrdom video of the kind favoured by Hamas. He did not even tell his family his plan, although they had seen a change in him over the three days since the revolution began.

Ziu不是一名通常的自杀式袭击者。他是一名国家石油公司的高管,身材矮小,有些秃顶,娶了本地女人为妻。他没有哈马斯喜欢搞的那种殉难视频。他甚至没有把自己的计划告诉家人,虽然家人们已经发现在革命开始的三天里他有些异样。

"He said everyone should fight for the revolution: 'We need Jihad,'" says Ziu's 20-year-old daughter, Zuhur, clearly torn between pride at her father's martyrdom and his loss. "He wasn't an extreme man. He didn't like politics. But he was ready to do something. We didn't know it would be that."

“他说人人都应为革命而战:‘我们需要圣战’”,Ziu 20岁的女儿Zuhur,还迷失在为父亲英勇就义的骄傲和失去父亲的悲痛中。“他并不是一个极端的人,他不喜欢派别之争,但是他已经做好准备,只是我们不知道会是这样。”

Ziu may have been unusual as a suicide bomber, but he was representative of a revolution driven by dentists and accountants, lorry drivers and academics, the better off and the very poor, the devout and secular. Men such as Abdullah Fasi, an engineering student who had just graduated and was in a hurry to get out of a country he regarded as devoid of all hope until he found himself outside the Katiba stoning Gaddafi's soldiers. And Shams Din Fadelala, a gardener in the city's public parks who supported the Libyan leader up to the day government soldiers started killing people on the streets of Benghazi. And Mohammed Darrat, who spent 18 years in Gaddafi's prisons and every moment out of them believing that one day the people would rise up.

Ziu作为一个自杀式袭击者或许不同寻常,但他是一场革命的代表者,这场革命由牙医和会计师,卡车司机和学者,富人和穷人,上层人士和平民百姓一同发起。Abdullah Fasi,一位刚刚毕业的理工科学生,正欲逃离这个他认为毫无希望的国家,直到他来到Katiba城外,将石块扔向卡扎菲的军队。还有Shams Din Fadelala,一个公园的园丁,他一直支持利比亚的领导人,直到government的军队开始在班加西的大街上杀害平民。还有Mohammed Darrat,他在卡扎菲的监狱里呆了18年,时时刻刻都坚信人民终会揭竿而起。

Fasi joined the revolution on day two. The protests began after sunset on 15 February outside the police headquarters to demand the release of a lawyer, Fathi Terbil, who was arrested over a lawsuit against the government on behalf of the relatives of 1,200 men killed by Gaddafi's forces at Abu Salim prison in 1996. Relatives of the dead men and lawyer friends of Terbil started to march. As they moved through the city, the crowd swelled and chanted slogans from the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions. The police attacked them with water cannon and the government unleashed young men wielding broken bottles and clubs against the protesters. All that did was to bring thousands more on to the streets the next day, including Fasi.

Fasi在第二天加入了革命队伍。示威于2月15日在一所警察局外开始,他们要求释放一个名叫Fathi Terbil 的律师,他在代理一场和government的诉讼中被捕,委托他的是1996年被卡扎菲的军队杀死在监狱里的1200人的亲属。死者的亲属和Terbil的律师朋友们开始了游行。当他们穿过城市时,人群迅速壮大,他们喊着突尼斯和埃及革命的口号。警察动用了水炮,government还派出了手持碎酒瓶和棍子的年轻人。这一切导致第二天更多的人走上街头,包括Fasi。

"At first we didn't ask Gaddafi to leave," he says. "We just wanted a constitution, justice, a better future. Then they came shooting and beating the people. After that we said Gaddafi must leave."

"I knew I had to go to the Katiba. They were shooting us. In front of me they killed seven people in those four days. The last day was very very hard. People started to get TNT from the other camps and make the fish bombs. Every five minutes I heard a fish bomb explode."

“一开始我们并不希望卡扎菲下台”,他说,“我们只是想要宪法、正义、和更好的未来。然后他们就开始射击和殴打。之后我们就认为卡扎菲必须下台”。“我知道我必须去Katiba,他们在朝我们开枪。我亲眼看到他们在这4天里杀了7个人。最后一天尤为艰难,人们开始从其他兵营得到炸药制造鱼弹,每5分钟我就能听到鱼弹爆炸的声音”

With the battle of the Katiba won and the revolutionaries in control of Benghazi, Fasi gravitated toward the city's courthouse on the dilapidated Mediterranean sea front, a mix of ornate Italian colonial-era buildings and ugly but functional modern constructs. The revolutionaries had burned the court and the neighbouring internal security offices as symbols of repression. Now they were rallying centres and something of a shrine. Relatives of Gaddafi's many victims over four decades pinned up hundreds of pictures of the dead on the courthouse walls alongside those killed around the Katiba. Ziu's portrait is there as an heroic martyr. While some mourned, others let loose with graffiti plastered across Benghazi declaring that the 42-year nightmare was nearly over.

Katiba之战胜利后,义军控制了班加西,Fasi去了位于地中海岸边的市法院大楼,一栋融合了意大利殖民时期华丽风格和丑陋但实用的现代部件的大楼。义军烧毁了法院和相邻的安全局,因为他们是压迫的象征。现在他们在市中心集结。40几年来被卡扎菲杀死的受害者的亲属们将死者的照片贴满了法院大楼的墙上。作为英雄的烈士,Ziu的肖像也在那里。有的人在哀悼,其他人则在班加西的墙上涂写标语,宣告42年的噩梦即将结束。

Benghazians still marvel at their own courage in taking on the regime. Failure would almost certainly have meant execution, years in one of Gaddafi's brutal prisons or exile. Yet otherwise ordinary people inspired each other to take the risk, not for an ideological cause or over some ethnic divide but to enjoy the basic freedoms few have ever known.

班加西人仍然惊讶于自己推翻政权的勇气。失败将毫无疑问意味着处死、在卡扎菲恐怖的监狱里被关数年或被驱逐。但是人们互相鼓励,决定要冒这个险,不是因为意识形态或者种族,而是为了享受几乎无人听说过的自由。

2011年4月,一位班加西义军站在Katiba兵营的废墟上

Middle-aged men said they stood against Gaddafi because they couldn't bear the thought of their children growing up to face a future devoid of hope. Younger people spoke of a realisation that they could either seize the moment or resign themselves to a half-existence under the tutelage of the next generation of Gaddafis. Even a few weeks later when the regime's tanks were at the gates of Benghazi and the revolution looked as if it might be lost, expressions of regret were rare. The hardcore of revolutionaries — the female dentistry professor with an eight year-old child, the accountant with a family in the US, the shopkeeper who wonders where the money to feed his family will come from because the revolution has killed trade all said that at least they would die as free Libyans.

中年人起来反抗卡扎菲,因为他们不能忍受自己的孩子长大后要面对一个毫无希望的未来。年轻人则认识到他们要么抓住机会,要么苟活在下一代卡扎菲家族成员的统治下。即便几个星期后卡扎菲的坦克兵临班加西城下,革命看起来就要失败的时候,也罕有后悔的神情。革命的中坚力量——一位有8岁孩子的女牙科医生,一位在美国有家庭的会计师,和一位因革命造成贸易中断而不知养家的钱从哪里来的店主,纷纷表示他们至少会作为自由的利比亚人而死去。

Few revolutions have been more inspiring. After years of reporting uprisings and conflicts driven by ideology, factional interests or warlords soaked in blood — from El Salvador to Somalia, Congo and Liberia – Libya's uprising seems to me more akin to South Africa's liberation from apartheid. For a start, the once pervasive fear of a hated regime is gone.

再也没有比这更为令人欢欣鼓舞的革命了。我数年间报道了因意识形态、派别利益或者军阀混战而导致的不同的骚乱和冲突——从萨尔瓦多到索马里,从刚果到利比里亚——利比亚的起义与南非人民摆脱种族隔离的解放运动更为相似。

From the first days, scores of enthusiastic young revolutionaries, high on the prospect of looming victory, indulged the newfound freedom to finally say what they thought. They churned out screeds listing the dictator's crimes and posters caricaturing Gaddafi as a common thief and agent of Mossad. Some posters imagined him on trial before the international criminal court or strung up on one of the gallows used for public hangings to terrorise the Libyan population.

从第一天开始,成群结队热情似火的革命者,幻想着革命必将成功的前景,沉醉在他们新发现的言论自由里无法自拔。他们撰文列举独裁者的罪行,制作将卡扎菲画成窃贼和摩萨德代理人的漫画像。有的海报设想其在国际刑事法庭受审,或是站在其为恐吓利比亚人民用作当众处死刑具的绞刑架上。

Revolutionary committees sprang up. Among them was one charged with getting the message to the outside world that Libya 2011 was not Tehran 1979. The savvy revolutionary activists watching CNN and news websites were not slow in recognising the fearmongering in parts of the US media and Congress over what kind of revolution this was.

革命委员会成立了。其中一位成员曾被控向外传播消息,称2011年的利比亚不是1979年的德黑兰。聪明的革命积极分子观看CNN和其它新闻网站,他们在认识这次革命的性质时并不比美国的媒体和议会落后。

Almost the only foreigners in Benghazi during the early days of the revolution were journalists. We were feted with free coffee in cafés and regularly stopped on the street and thanked for coming. But reporters were also quizzed by Libyans who picked up on the talk about Islamic extremists hijacking the revolution. Where, they wondered, did the idea of al-Qaeda in Libya come from? Couldn't people see what kind of revolution this is?

革命前期,在班加西的外国人几乎只有记者。我们有免费咖啡供应,还经常在大街上被人拦下,说谢谢我们的到来。但是记者们也会面临利比亚人民的关于伊斯兰教极端分子绑架革命的问询。他们想知道,利比亚存在基地组织的想法是从哪里来的?难道人们都看不明白这到底是一场什么样的革命吗?

It is hard not to notice how desperate the core of revolutionaries is to be accepted by the west. It is common enough to run into accountants, oil executives and engineers on the frontline who have studied in Nottingham, Manchester and Brighton. They say they admire Britain and the US. Denunciations of America are noticeably absent, at least on the rebel side of the line. France's president, Nicolas Sarkozy, is a hero in rebel-held areas for recognising the revolutionary administration.

如果你对革命的中坚分子对其被西方社会接受的绝望视而不见,那是很难的。你在前线遇到会计师、石油公司的高管和工程师是很正常的事情,他们可能在诺丁汉、曼彻斯特或者布莱顿留过学。他们说他们很羡慕英国和美国。很明显对美国的指责是不存在的,至少在义军一方是这样的。因为承认了义军当局,法国总统萨科齐在义军占领区是一位英雄,

Yet it is also not hard to see why the outside world was uncertain about the revolutionaries. No other country in the Middle East is quite so defined by its leader.

同样不难发现的是,为何外界对革命者始终心存芥蒂。中东的其他国家领导人(当时)都没有表达如此明确的立场。

The cult of Gaddafi and his Green Book, his links to terrorism and the sheer brutality of a regime that publicly hanged students at Benghazi university for dissent, left little to be admired. The Libyan leader's colourful behaviour, including a taste for Amazonian bodyguards, led much of the world to conclude that he was unstable as well as dangerous. From the outside, there were good reasons to wonder if the collective sanity of the Libyan people had not gone off the rails in those 42 years, especially when Libyans were seen on television in near hysterics as they fanatically waved Gaddafi's green flag and swore to die for him.

对卡扎菲及其绿皮书的狂热,如此恐怖和残暴以至于会在班加西大学公开处决异见学生的统治,已经让人毫无留恋了。利比亚领导人的种种做派,包括对女子保镖的兴趣,让外界认为他是喜怒无常而又非常危险的。在外界看来,在经过42年之后,对利比人民的心智是否还是正常的感到疑惑是理所当然的,尤其是当在电视上看到利比亚人狂热地挥舞着卡扎菲的绿皮书发誓为他而死时那接近歇斯底里的状态时。

"He made us ashamed of our country. He made us ashamed of ourselves," says Mohammed Darrat, the former army officer who, in joining the throngs outside the Benghazi courthouse during the first days of the revolution, committed his first political act since Gaddafi flung him into jail in 1970. "Gaddafi gave this image to the world of the Libyan people as criminals or fanatics. It wasn't true. We knew all along that he didn't speak for us. It was always the people of Libya versus one family, the Gaddafis."

“他让我们为自己的国家感到羞耻。让我们为自己感到羞耻”,在革命开始的第一天里加入到班加西法院大楼外的人群时,前军官Mohammed Darrat这样说道,这是自1970年卡扎菲将他入狱后他的首次政治行动。“卡扎菲给外界的印象是利比亚人民都是罪犯,或者狂热分子,这不是真实的。我们从一开始就知道他是不会为我们说话的,利比亚人民同卡扎菲家族总是彼此对立的”。

That may not be entirely true. Many Libyans did very nicely out of the regime, at the price of unyielding loyalty to the "brother leader". But it is true that large numbers of Libyans regarded Gaddafi with contempt. Fasi, 23, grew up listening to his parents talk of Gaddafi as mentally unstable. "They thought he was mad – all my family talking about him and what he did in the 70s and 80s. They regarded him as a criminal for Lockerbie and a lot of other things. They hated it that the rest of the world only saw Gaddafi and not the Libyan people," he says.

这种说法可能并不完全正确。只要坚定地忠于“兄弟般的领袖”,许多利比亚人在这个政权下生活地很好。但是有相当一部分利比亚人确实瞧不起卡扎菲。23岁的Fasi从小就听他的父母说卡扎菲如何神经错乱。“他们认为他是个疯子——我的家人都会谈起他和他在七、八十年代做的事情。他们认为他是洛克比和其他好多恶行的罪魁祸首。他们厌恶外界只知道卡扎菲而无视利比亚人民”,他说。

Fasi was warned by his parents never to repeat such views outside the house. That didn't stop him. "For my generation, we were talking about it a lot. You can't say Gaddafi is mad to just anybody. You can say it to close friends, but not to someone you don't know properly, in case he's a spy for internal security. In the last few years we were talking about that a lot among ourselves, saying we don't want Gaddafi. But none of us expected Gaddafi to fall. Everybody was waiting for him to die. We left it to God to deal with him and we told ourselves whatever happens after there can be no one worse than Gaddafi," he says.

Fasi的父母警告他不要在外面说这些话,但这没能阻止他。“对我这一代人来说,谈论这些事情是经常的。你不能对所有人都说卡扎菲是个疯子,对很亲近的朋友是可以的,但对不明底细的人就不可以,以防他是安全局的间谍。最近几年我们谈了很多这些事儿,说我们不想要卡扎菲了,但我们都不希望卡扎菲下台,每个人都在等他死去。我们把对付他的任务交给上帝去解决,我们对自己说,那以后不管发生什么,都不会有比卡扎菲更坏的人了”他说。

Until that day, many young Libyans saw no future in their own country. They were generally less concerned with Gaddafi's crimes against his own people — Benghazi was a favoured place for public hangings of political dissidents — than with the despair of living in a country where they saw no future. "I had to join the revolution because we didn't have any hope here," says Fasi. "A lot of my friends left the country after graduation. You see the outside, you see the other countries, you see how they live free. Even if their economies are bad, they are free. That's the point."

直到那一天,利比亚的许多年轻人才看到了自己国家未来的希望。相对于卡扎菲对自己的人民所犯下的罪行——班加西是公开处决政治异见人士的理想之所,他们通常更关心生活在一个看不到未来的国度里的绝望情绪。“我要参加革命,因为这里我们看不到任何希望”,Fasi说道。“我的许多朋友毕业后都出国了,看看外面,看看其他国家,看看他们是如何自由生活的。虽然他们的经济状况并不好,但他们是自由的。这才是关键”。

For Darrat, the revolution is about something else entirely. It's personal. He knew Gaddafi from their army days, recognised the nature of the man and turned against him almost from the moment he seized power in 1969. "I went to military academy in Iraq. I saw that revolution and all the suffering there, the crimes," he says. "After Gaddafi's revolution I joined a secret group of army officers. We watched a lot of soldiers in the upper ranks behaving immorally, harming people because they wanted power. Because of what I had seen in Iraq I thought the same terrible things would happen here. I was right."

对Darrat来说,革命就是全然不同的东西。那是关乎个人的。他从军时开始熟悉卡扎菲,认识他的品性,并且几乎从他1969年掌权是就反对他。“我去了伊拉克的军校,我看到了那次革命和所有的苦难,那些罪行,”他说。“在卡扎菲革命后,我加入了一个由军官组成的秘密组织。我们发现了很多上层军官的放荡行为,为了争权夺利不惜鱼肉百姓。由于在伊拉克的所见所闻,我想同样的事情在这里也会发生。结果我说对了”。

Darrat joined a clique of officers planning to overthrow Gaddafi, but after a few months they were betrayed and arrested. "Gaddafi said we were traitors. They showed no humanity. They beat us day after day to obtain information. They smashed my leg and my back. I couldn't walk," he said.

Darrat加入了一个计划推翻卡扎菲的军官组织,但几个月后,他们被出卖并逮捕。“卡扎菲说我们是卖国贼,他们毫无人性,没日没夜地殴打我们以获取信息。他们打断了我的腿和后背,我走不了路了,”他说。

Darrat was sentenced to life in prison. He left behind a wife and four children. Hundreds of other military personnel were also jailed. He describes prison as "very, very bad". After two operations to repair the damage done by the beatings to his legs and back he was immediately returned to his cell without anything to control the pain.

Darrat 被判终身监禁,撇下妻子和四个孩子。数百名其他军人也被关进监狱。他用“非常非常糟糕”来形容监狱的状况。他做了两次手术,医治被打伤的腿和背部,然后在没有任何缓解疼痛的措施的情况下被立刻送回了监狱。

Darrat brings out a picture of his military academy graduation class. In it is one of the army officers who brought Gaddafi to power in the 1969 coup. Another in the group was executed for opposing the Libyan leader. He has no idea why Gaddafi freed him early. "Who knows what Gaddafi thinks," he says. "I don't know how we allowed him to take control of our lives. We could all see what he was."

Darrat拿出了一张他在军校的毕业照。其中有一名军官在1969年的革命中将卡扎菲推上王位,另一人因反对利比亚领袖而被处死。他不清楚为何卡扎菲提前将他放了出来。“谁知道卡扎菲在想什么?”他说“我不知道为何我们会将性命交付于他,我们都清楚他是个什么东西”。

When Gaddafi seized power he promised to do more for the poor with his distinctive brand of socialism. Wealthier Libyans lost properties. People in rented accommodation were told it now belonged to them. Yet for all the ideological rhetoric a substantial part of Libya's population still lives in poverty.

卡扎菲掌权时他承诺用他鲜明的社会主义标签为穷人做更多事情。利比亚的富人们失去了财产,租房居住的人们则被告知房子是他们的了。尽管如此,在意识形态的浮夸下,绝大多数利比亚人仍然生活在贫困之中。

In a corner of Benghazi rarely seen by its better-off residents is a warren of roughly constructed shacks and containers made into houses. Shams Din Fadelala built his own place from breeze blocks and corrugated iron on a piece of barren land that was once the compound of a German oil company. From the outside, the house does not have an air of permanence. Inside it is immaculately turned out with china models of flowers and birds on the coffee table.

在班加西,一个富人们极少注意到的角落里,有一个简易搭建的棚户区。Shams Din Fadelala用小木块和旧铁皮在一块原来是一座德国石油工厂的贫瘠土地上搭建了自己的房子。从外面看,房子毫不起眼,里面却很整洁,咖啡桌上放着瓷质花鸟。

Fadelala says he had lived much of his life without expectations. Gaddafi's Libya did not encourage hope for a better life. The only real ambition for many Libyans was to stay out of the hands of the dictator's notorious security police and find a job abroad. But Fadelala could not even cling to that small dream. As a gardener in Benghazi's parks, he earns just £90 a month ("I give it all to my wife," he says).

Fadelala说他大多数时候都过着毫无期望的生活。卡扎菲的利比亚并不鼓励人们对美好生活的向往。很多利比亚人仅有的一点雄心是躲开独裁者臭名昭著的安全警察,在外面找份工作。但Fadelala连这点梦想也无法实现。作为班加西一所公园的园丁,他每月挣90英镑(“我把钱全部给我老婆了,”他说)。

None of that stopped him from supporting Gaddafi. "I had always supported Gaddafi," he says. "There was no one else, so who else could I support? He was the leader."

这些都没能阻止他支持卡扎菲,“我一直支持卡扎菲,”他说,“没有其他人,我能支持谁呢?他是领袖”。

As Fadelala watched the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions on al-Jazeera he marvelled at the audacity of the revolutionaries while not entertaining a flicker of hope that the same thing could happen in Libya. "It was interesting but I though it could never happen here. This is a different country. They didn't have Gaddafi," he says.

当Fadelala看到突尼斯和埃及发生的革命运动时,他惊异于革命者的勇气,但他从来不曾有过哪怕一丝念头——同样的事情会在利比亚发生。“那很有意思,但是永远也不会在这儿发生,这个国家是不同的,他们没有卡扎菲,”他说。

The regime calculated that unleashing violence against the protesters would intimidate men like Fadelala from supporting the revolutionaries. It was wrong. By the second day of the revolution, Fadelala was so appalled at the violence that he took the first political stand in his life and went to the courthouse in solidarity with the revolution. "When I saw what was happening, the shooting of protesters at the Katiba, I thought: 'No more Gaddafi'. People were just protesting. He had no right to kill them for that," he says.

government的算盘是动用暴徒镇压抗议者,像Fadelala这样的人就会被吓得不敢支持革命了。他们错了。革命开始的第二天,Fadelala就同示威者一起,冲向了大院大楼,从而有了他生命中的第一个政治立场。“当我看到发生的一切,在Katiba对示威者开枪,我想:‘再见吧卡扎菲’。他们仅仅是抗议而已,他没有权力因为这个杀掉他们,”他说。

Fadelala was not alone. Plenty of Benghazians eyed the uprising with suspicion, worried at the breakdown of order. But Gaddafi's reaction — to slaughter protesters and accuse those demanding democratic freedoms of being drug addicts and members of al-Qaeda — revived memories of the most brutal years of the dictator's rule in the 1980s and bolstered support for the uprising.

Fadelala并非特例。许多班加西市民也用怀疑的态度看待起义,担心陷入混乱。但是,卡扎菲的反应——屠杀示威者,指责那些要求民主自由的人是吃了药物或者是基地组织的成员——让他们想起了这个独裁者在19世纪80年代那些最野蛮日子的记忆,于是愤而支持起义。

The revolution has still to be won. Gaddafi controls more territory than the revolutionaries. He managed to get his tanks into Benghazi before western air strikes drove them back. The residents of "free Libya" are in the peculiar position of being the only people on the planet pleading with foreigners to bomb their country.

革命尚未成功。卡扎菲仍然比革命者占据更多的地盘。他计划在西方的空袭将他们赶回去之前,把他的坦克开进班加西。“自由利比亚”的居民们正站在一个非常奇异的立场上——他们成为这个星球上唯一请求外国人轰炸自己祖国的人民。

Yet the uprising has changed everything. The fear of the regime is gone. The revolution has exposed the myth of Gaddafi's invincibility even if he manages to hang on for another few months. Fasi says he now has a reason to stay in Libya. "I really want to share in building this country," he says. "It's a dream to be the best country in the world. We can be that now. I think it needs democracy, and this country is rich. Democracy and oil, that's all we need."

但是,起义已经改变了一切。对政权的恐惧已经荡然无存。革命已经打破了卡扎菲无往不胜的神话,尽管他还能再挣扎几个月。Fasi说现在他有理由留在利比亚了。“我真的希望在这个国家的建设中出一份力”,他说,“成为世界上最好的国家,这是一个梦想。我们现在能做到了。我想这需要民主,这个国家非常富有。民主和石油,这就是我们需要的东西”。

Ziu的照片,现在在班加西到处可以看见。当地人叫他“班加西英雄”

插图和插图说明均为老榕添加。照片由志愿者提供。